Systemic reviews on implantable medical devices provide a quality of reporting

July 12, 2021

How to write a case report

July 19, 2021In brief

Abstract screening is an integral part of doing an efficient and thorough systematic examination. The necessary first step in synthesizing the existing literature is abstract scanning, which helps the review team narrow down the vast amalgamation of citations found across academic libraries to the citations that should be “full text” screened and ultimately used in the review(1).

Introduction

Conducting a thorough analysis, no matter how big or small, necessitates meticulous preparation, meticulous data recording, and continuous administrative supervision. 1 A high-quality analysis depends on the experience of a group of material and methodological members, as well as information gained from previous reviews.Identifying studies suitable for evaluating and screening these studies to identify others eligible for review is a major activity of a systematic review. A high-quality systematic analysis requires searching for and finding a wide variety of research.

In the social sciences, systematic analysis teams face difficulty in that certain study issues cross academic lines, necessitating multiple disciplinary and cross-sectional datasets to search for applicable findings. Domain searches yielding over 5000 results are common in psychology, education, criminal justice, and medicine (2).

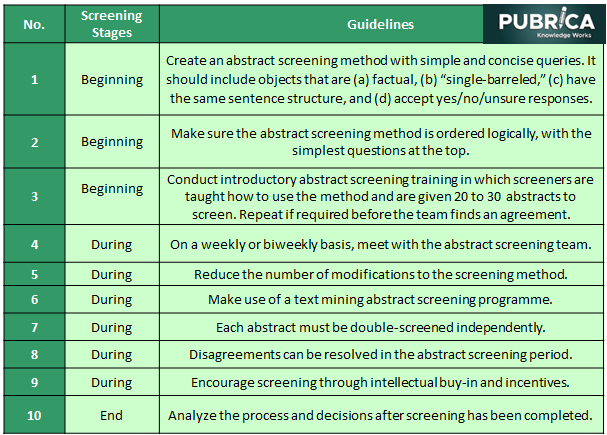

Table 1: Abstract screening process, for example, study

Table 1 summarises a synthesis of course instructions, expert discussions, and practical practice undertaking or engaging in various large-evidence systematic reviews.

Before screening begins

1. Create an abstract screening method for a systematic review with simple and concise queries. It should include objects that are (a) factual, (b) “single-barreled,” (c) have the same sentence structure, and (d) accept yes/no/unsure responses.

It is the first of many recommendations for the advancement of scanning and coding forms for systematic analysis that have been made over the years. The abstract screening method is dependent on the study’s inclusion criterion, which should be used in an analysis procedure created before the literature scan.

2. Ensure the abstract screening method is ordered logically, with the simplest questions at the top.

Screening a vast number of research abstracts would be a time-consuming process for review team members. Abstract screeners naturally want to go as fast as possible through the process and make assumptions on each abstract. Their pace also leads to fatigue: less fatigue means faster and more accurate abstract scanning; everything is equivalent.

3. Conduct introductory abstract screening training in which screeners are taught how to use the method and are given 20 to 30 abstracts to screen. Repeat if required before the team finds an agreement.

The abstract screening tool will be circulated to the abstract screening team once it has been developed. This team’s participants may or may not have prior experience screening abstracts. Regardless of the team members’ previous encounters, abstract screening preparation is important (3).

During abstract screening:

4. On a weekly or biweekly basis, meet with the abstract screening team.

The abstract screening team can meet regularly or every other week after the initial planning and piloting meetings are completed and the full team starts abstract screening in earnest. These meetings aim to foster a culture of debate, experimentation, and excitement while also reducing “coder drift.”

5. Reduce the number of modifications to the screening method.

As previously said, the abstract screening tool should be piloted and updated at the start of the abstract screening process. Explanations of the abstract screening tool should be deemed necessary and beneficial as more people scan abstracts and work in the pilot round. Screeners of abstracts should feel free to make improvements and call for clarification.

6. Make use of a text-mining abstract screening program.

Traditional abstract screening lists all citations for screening using reference management software (such as EndNote or Zotero) or simple spreadsheets. After that, the abstracts are screened in the order in which they were downloaded from database searches. The first abstract screened is likely the last abstract to be kept for full-text screening.

7. Each abstract must be double-screened independently.

Double-screening all available abstracts isn’t a new concept; it’s been recommended as best practice for decades. Single screening has the power to rule out trials until they have been thoroughly vetted. It’s just too quick to make a blunder and lose a report.

- Disagreements can be resolved in the abstract screening period.

Screening disputes can arise no matter how successful the screening method is or how often the abstract screening committee meets. These are often the result of mere human error; other times, they result from“coder drift” or other structural problems.

- Encourage screeners by limiting time on task, promoting intellectual buy‐in, and providing incentives.

As previously said, abstract screening is a thankless and time-consuming process. As a result, analysis supervisors, like managers in other industries, must work diligently to keep abstract screeners motivated to continue screening on schedule and effectively (4).

After screening ends

- Analyze the process and decisions after screening has been completed.

The abstract scanning process culminates in a spreadsheet of decisions for each citation found. Completing abstract screening, particularly for massive proof programs, may feel like a significant achievement (5).

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to include a collection of realistic, abstract screening recommendations to literature review teams and administrators of broad evidence evaluations. Our instructions ensure that the abstract screening process is completed quickly and with the fewest possible mistakes. While we agree that these recommendations should be made accessible to the scientific community at large and that their use would encourage successful research syntheses, further research is needed to test our arguments (6).

References:

- Chai, Kevin EK, et al. “Research Screener: a machine learning tool to semi-automate abstract screening for systematic reviews.” Systematic Reviews 10.1 (2021): 1-13.

- Qin, Xuan, et al. “Natural language processing was effective in assisting rapid title and abstract screening when updating systematic reviews.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 133 (2021): 121-129.

- Wang, Zhen, et al. “Error rates of human reviewers during abstract screening in systematic reviews.” PloS one 15.1 (2020): e0227742.

- Harrison, Hannah, et al. “Software tools to support title and abstract screening for systematic reviews in healthcare: an evaluation.” BMC medical research methodology 20.1 (2020): 1-12.

- Clark, Justin, et al. “A full systematic review was completed in 2 weeks using automation tools: a case study.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 121 (2020): 81-90.

- Ritchie, Alison, et al. “Do randomized controlled trials relevant to pharmacy meet best practice standards for quality conduct and reporting? A systematic review.” International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 28.3 (2020): 220-232.