A Meta-Analysis of population studies on the prevalence of chronic pain in UK

January 12, 2022

In UK, an observational investigation on vitamin D and COVID-19 risk for Medical Research

January 17, 2022Growing financial and service demands in the UK National Health Service (NHS) have been argued to need a transformation in health and social care. The NHS Five Year Forward View Plan, issued in 2014, outlines how services must evolve and emphasizes the need for greater care integration. Increased service integration, it is suggested, will enable the NHS to develop a financially sustainable health and social care system by 2020. More care beyond the hospital walls, changes in the size and design of acute hospitals, and increased attention to prevention and public health are goals of the new integrated care model. This systematic review aimed at the effects of these new integration models and research into whether models used in other care systems may achieve similar results in the UK National Health Service setting.

Methods

Complex system-wide projects, such as integrated care models, provide substantial challenges for systematic review approaches. Randomized experimental trials, known as the “gold standard,” have historically been employed in systematic reviews to look for unambiguous intervention-outcome effects. However, there has been significant growth in the number of review methods accessible in recent years. It has become evident that different review types are best for addressing additional questions and fulfilling different aims. To accomplish the three goals of analyzing various forms of integrated care initiatives and service delivery results, combining studies of varied designs across the hierarchy of evidence, and learning most relevant to the NHS in the United Kingdom, we used a proper review technique. As a result, we adopted a technique based on Pawson’s work, which emphasizes the necessity of accuracy and relevance when analyzing complex outcome patterns.

Guidelines from the Cochrane Collaboration, the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care, and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database were used in this systematic review research. We used Medline, Embase, ISI Web of Knowledge, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus to search five databases. In each database, twenty-five expressions were entered (see supplementary material). We also used Google to search the Internet, contacted specialists, and evaluated reference lists.

Literature Review search strategy

The study protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database and available on the National Institute for Health Research website. The conducting of literature review was conducted according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.

Collecting data for Literature Review

Three reviewers assessed publication titles and abstracts (where available) against the inclusion/exclusion criteria after the citations were submitted to an EndNote database. The entire team discussed any issues about inclusion at regular (fortnightly) team meetings.

Evaluation of the risk of bias

The hierarchy of research design and various checklists for each study type were utilized to assess quality. We investigated for sources of potential bias in studies that employed a comparative method using the Cochrane criteria (selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, detection bias, reporting bias). We followed the National Institutes of Health recommendations when using studies before and after (pre-post) designs with no comparison group or published systematic reviews. Instead of a numerical quality indicator, we did not evaluate elements but offered a narrative.

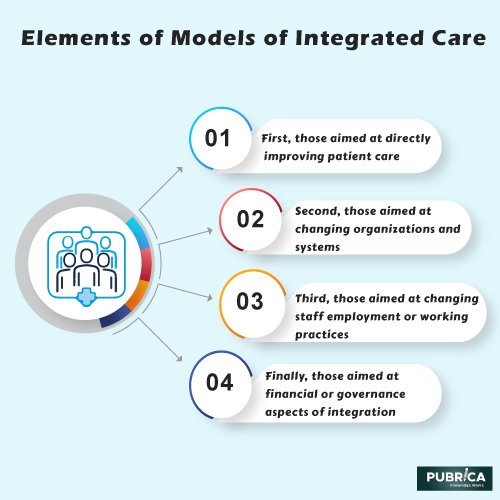

Elements of models of integrated care

The majority of the integrated care models considered were multi-element and sophisticated interventions. The elements within them could be divided into four categories: first, those aimed at directly improving patient care; second, those aimed at changing organizations and systems; third, those aimed at changing staff employment or working practices; and finally, those aimed at financial or governance aspects of integration. Due to restricted reporting, many models included many elements, making it difficult to decipher the form and components. We found the most elements in a single intervention to be nine, higher than comparable integrated care efforts with only one element. Models typically had four to six elements. In the international research, case manager/case co-coordinator initiatives were more common, but integrated care pathways/plans were more common in UK models.

Conclusion

Pubrica encourages systematic review services, although the evidence for other objectives such as service costs is uncertain, integrated care models may improve patient happiness, raise the perceived quality of care, and permit access to services. Improved access might significantly impact services that fail to meet rising demand.

Reference

- Susan Baxter, Maxine Johnson, Duncan Chambers, Anthea Sutton, Elizabeth Goyder & Andrew Booth; The effects of integrated care: a systematic review of UK and international evidence; BMC Health Services Research volume 18, Article number: 350 (2018).

- Shoou-Yih Daniel Lee, Bryan J. Weiner, Michael I. Harrison, C. Michael Belden Organizational Transformation: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research in Health Care and Other Industries; https://doi.org/