How to Evaluate Scientific Grant Review Proposals

November 6, 2021

How to Conduct Meta-Analysis and Analysis Data

November 18, 2021In brief

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are not the same as traditional clinical review papers, usually known as updates. Updates evaluate the medical literature selectively while covering a broad topic for Physician Writing. Nonquantitative systematic reviews analyze the medical literature in depth, attempting to find and synthesize all relevant data to establish the optimal diagnostic or treatment strategy. Meta-analyses (systematic quantitative reviews) utilize sophisticated statistical analysis of pooled research papers to address a specific clinical question. The guidelines for authoring an evidence-based clinical review article for physicians are presented in this article.

Introduction

The most acceptable clinical review articles base their discussions on current systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and they include all relevant research results on how to treat a specific condition. These evidence-based updates give readers concise summaries as well as solid therapeutic advice. Criteria for producing an evidence-based clinical review article, particularly one intended for continuing medical education (CME) and include CME objectives in its structure. The article’s bias, a lack of adequate supporting evidence, or other considerations to conduct a study of the Literature review methodologies and, when possible, assign a score to essential pieces of evidence. This method helps to accentuate the article’s main themes.

Topic Selection

Choose a prevalent clinical condition and avoid themes that are rare or uncommon illness presentations or that are merely interesting for the sake of curiosity. Choose common issues for which there is new knowledge on diagnosis or therapy wherever possible. Recent data indicating spironolactone medication increases survival in patients with severe congestive heart failure, for example, might drive a clinical practice change if it is valid. Similarly, new evidence indicating that a narrative literature review of conventional treatment is no longer effective and may even be hazardous should be reported. Patching most acute corneal abrasions, for example, may exacerbate symptoms and delay healing.

Searching the Literature

Look for relevant recommendations on the condition being discussed’s diagnosis, treatment, or prevention. Include any high-quality suggestions that are related to the issue. Look for all primary Clinical Literature review suggestions concerning diagnosis and, especially, therapy in the initial draught. Attempt to ensure that all suggestions are based on the most up-to-date evidence.

Patient-Oriented vs Disease-Oriented Evidence

Patient-Oriented Evidence that Matters (POEM) is concerned with patient-relevant outcomes such as changes in morbidity, mortality, or quality of life. POEM-type evidence differs from disease-oriented evidence (DOE), which Systematic literature review focuses on surrogate endpoints such as test results or other response indicators. Indicate that foremost clinical advice lacks the backing of outcomes evidence when DOE is the only guideline provided.

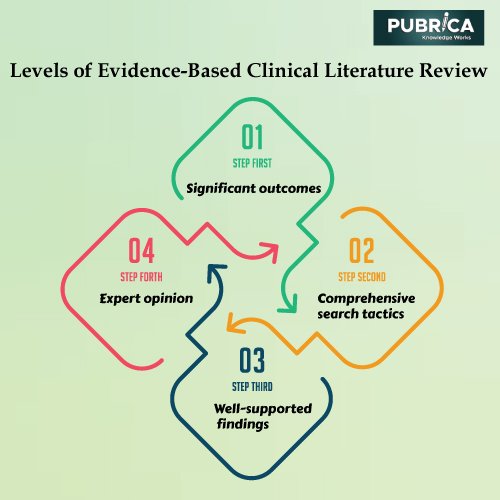

Levels of Evidence

The quality of the evidence supporting the essential clinical recommendations on diagnosis and therapy is critical information for readers. In the medical literature, several different grading systems of varying complexity and clinical usefulness are reported.

- Takes all significant outcomes Comprehensive search tactics were used to conduct a high-quality meta-analysis (systematic quantitative review).

- A comprehensive nonquantitative review with effective search tactics and well-supported findings. A well-designed, nonrandomized clinical study is considered Level B (other evidence). Lower-quality RCTs, clinical cohort studies, and case-controlled studies with non-biased participant selection and consistent findings are included. Other data, such as well-designed epidemiologic studies with compelling findings or high-quality, historical, uncontrolled investigations, is also included.

- Level C (consensus/expert opinion): Expert opinion or consensus position.

Format of the Review

INTRODUCTION

The review’s topic and objective should be defined in the introduction and its relevance to family practice. The natural way of achieving this is to talk about the disease’s epidemiology, which includes how many individuals have it at any particular moment (prevalence) and what percentage of the population is projected to get it over time (incidence). A more exciting approach to accomplish this is to show how many times a regular family physician meet this problem in a week, month, year, or career. Emphasize and summarise the review’s primary CME objectives in a separate table labelled “CME Objectives.”

METHODS

The methodology section should briefly describe how the literature search was carried out and the primary evidence sources. Indicate which studies were included or excluded based on predefined criteria (e.g., studies had to be independently rated as high quality by an established evaluation process, such as the Cochrane Collaboration). Make a thorough effort to locate all significant relevant research. Avoid using solely the material that supports your findings as a reference. If an issue is controversial, discuss the entire extent of the argument.

DISCUSSION

After then, the discussion might take on the shape of a clinical review article. It should cover aetiology, clinical presentation (signs and symptoms), pathophysiology, diagnostic evaluation (history, physical examination, diagnostic imaging, laboratory evaluation, and), differential diagnosis, treatment (goals, medical/surgical therapy, laboratory testing, patient education, and follow-up), prognosis, prevention, and future directions).

REFERENCES

The references should contain the most current and essential sources of support (i.e., studies referred to, controversial material, new information, specific quantitative data, and information that would not usually be found in most general reference textbooks). These usually are significant evidence-based recommendations, meta-analyses, or Systematic literature reviews, seminal studies. While other journals publish lengthy lists of reference citations, AFP prefers to provide a concise list of relevant references.

Conclusion

Evidence-based evaluations may help select how to deploy health-care services, particularly preventative programmes, in some instances. Some high-quality cost-effectiveness studies were appropriate to assist understand the costs and health benefits of various strategies for achieving a particular health result. In the discussion, highlight significant aspects concerning diagnosis and therapy. These points are not always the same as the significant recommendations, which are ranked according to their degree of evidence.

About Pubrica

Pubrica Has a Professional Experience in Medical Writing. Further, The Team of Medical Professionals from Pubrica, Offer Unique Medical Writing Services, Includes Clinical Research, Pharmacology, Public Health, Regulatory Writing, Clinical Report Medical Device, Pharmaceutical, Nutraceutical, Hospitals, Universities, Publishers, PhD, Students Pursuing Medicine, Physicians, Doctors, Authors and Provide Support in Writing Any Medical Stream Paper.

References

- Siwek J, Gourlay ML, Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. How to write an evidence-based clinical review article. Am Fam Physician. 2002 Jan 15;65(2):251-8. PMID: 11820489.

- Medic, Goran, et al. “Evidence-based Clinical Decision Support Systems for the prediction and detection of three disease states in critical care: A systematic literature review.” F1000Research 8 (2019).

- Horntvedt, May-Elin T., et al. “Strategies for teaching evidence-based practice in nursing education: a thematic literature review.” BMC medical education 18.1 (2018): 1-11.

- Leonard, Elizabeth, Imke de Kock, and Wouter Bam. “Barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based health innovations in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic literature review.” Evaluation and Program Planning 82 (2020): 101832.