Reasons behind the production of defected tablets through various processes

August 9, 2021

Recent technologies and future perspectives in cancer therapies

August 16, 2021In brief

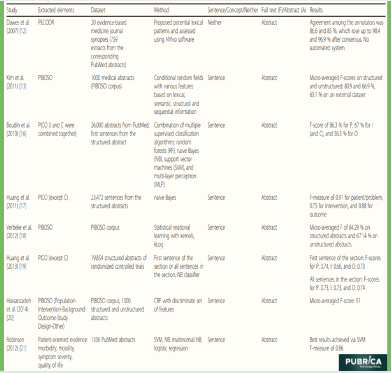

Data should be extracted based on previously identified interventions and outcomes developed during the formulation of the study topic, inclusion/exclusion requirements, and search procedure. It should not be challenging to classify the data elements that need to be retrieved from each included sample if those phases have been completed properly. To analyze and assess findings, extract data from related studies. It is important to use sound data collection techniques when the data is being collected (1). Data processing can begin as soon as you begin collecting data, and it can even determine which data types you retain.

Introduction

Researchers in evidence-based medicine are overwhelmed by the volume of primary research papers, both old and modern. Since it is currently impractical to scan for appropriate data with accuracy, support for the early stages of the systematic review phase – searching and screening studies for eligibility – is needed. Not only could better automatic data extraction help with the stage of analysis known as “data extraction,” but it could also help with other aspects of the review process.

Systematic review (semi)automation research lies at the intersection between evidence-based medicine and computer science. Besides the advancement in computing power and storage space, computers’ capacity to serve humans grows. Data extraction for systematic analysis is a time-consuming process (2). It opens up possibilities for sophisticated machines to assist. In this domain, tools and methods are often based on automating data processing relevant to the PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcome).

Table 1 A summary of included extraction methods and their evaluation

Work Flow and study design

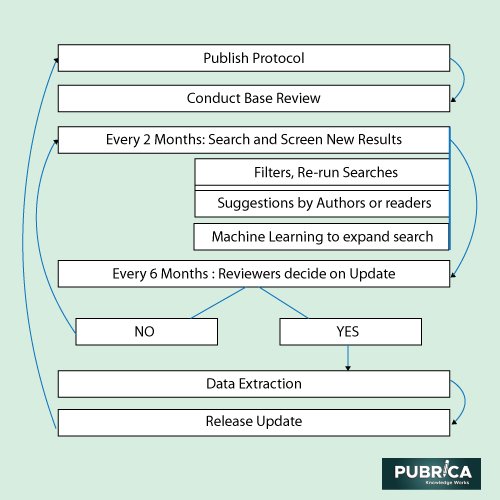

Two critics will separately screen both titles and abstracts. Any discrepancies in judgement would be addressed and, if possible, overcome with the assistance of a third reviewer. The evaluation process for complete texts would be the same, a single reviewer will extract data, and a random 10% selection from each reviewer will be reviewed separately. We plan to contact the writers of reports for confirmation or additional material if necessary. We will provide a cross-sectional overview of the data from our searches in the case study and any published update. The analysis will include the features of each reviewed method or tool, as well as a summary of our outcomes. In addition, we will evaluate the quality of reporting at the publication level (3).

Eligibility criteria

- Eligible papers

- Full-text articles describing an initial natural language processing method to extract data for structured reviewing activities will be included. The Extended data contains data areas of concern adapted from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The whole spectrum of natural language processing (NLP) techniques includes regular expressions, rule-based structures, machine learning, and deep artificialnetworks.

- Papers must detail the whole process of implementing and evaluating a system.

- The data used for mining in the included articles must be abstracts, conference proceedings, full texts, or portions of full texts from randomized clinical experiments, comparative cohort studies, or case management articles in the form of abstracts, conference proceedings, full texts, or parts of full texts.

- Ineligible papers

We will exclude papers reporting:

- image editing and downloading biomedical data from PDF files without the use of natural language processing (NLP), including data retrieval from graphs;

- any study that focuses merely on protocol planning, synthesis of previously extracted data, write-up, text pre-processing, and dissemination will be disqualified;

- Methods or tools that do not use natural language processing and instead focus on administrative interfaces, document storage, databases, or version control; or

• All articles relating to electronic health records or genomic data mining may be disqualified.

Key items for data extraction

Primary

Machine learning approaches used

Reported performance metrics used for evaluation

Type of data

- Scope: full text, abstract, or conference proceedings

- Study type: randomized clinical experiment, cohort, and case-control

- Input data format: For example, data imported as standardized results of literature searches (e.g. RIS), APIs, or data imported from PDF or text files.

- Output format: The format in which the data is exported after extraction is a text file.

Secondary:

- Data mining granularity: Does the machine retrieve individual entities, words, or whole sections of text?

- Other indicators that have been published, such as the effect on systemic review processes (e.g. time saved during data extraction)(4).

Limitations

First, there’s a chance that data extraction algorithms haven’t been published in journals or that our search has missed them. We searched several bibliographic databases, including PubMed, IEEExplore, and the ACM Digital Library, to overcome this limit. Second, we did not publish a protocol ahead of time, and our preliminary results may have affected our procedures. To eliminate potential bias in our systematic analysis, we duplicated main steps such as sampling, full-text review, and data extraction.

Future work

According to a systematic analysis, information retrieval technology positively affects physicians in decision-making—the need for new methods to report on and searching for organized data in written literature. The use of an automated knowledge extraction process to retrieve data elements can aid comprehensive reviewers and, in the long run, simplify the searching and data extraction steps (5).

Conclusions

The studies have described methods to extract these data elements, so data extraction for systematic reviews outlines previously reported methods to categorize sentences containing some of the data extraction elements. Data extraction approaches may serve as checks for currently conducted manual data extraction, then serve to verify manual data extraction achieved by a single reviewer, then become the primary source for data element extraction that a person will check, and finally full data extraction to allow live systematic reviews(6).

References

- Splieth, Christian H., et al. “How to intervene in the caries process: proximal caries in adolescents and adults—a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Clinical oral investigations 24.5 (2020): 1623-1636.

- Van Rensburg, Dina C. Christa Janse, et al. “How to manage travel fatigue and jet lag in athletes? A systematic review of interventions.” British journal of sports medicine 54.16 (2020): 960-968.

- Miake-Lye, Isomi M., et al. “Unpacking organizational readiness for change: an updated systematic review and content analysis of assessments.” BMC health services research 20.1 (2020): 106.

- Karunananthan, Sathya, et al. “PROTOCOL: When and how to replicate systematic reviews.” Campbell Systematic Reviews 16.2 (2020): e1087.

- Muka, Taulant, et al. “A 24-step guide on how to design, conduct, and successfully publish a systematic review and meta-analysis in medical research.” European journal of epidemiology 35.1 (2020): 49-60.

Haddaway, N. R., Bethel, A., Dicks, L. V., Koricheva, J., Macura, B., Petrokofsky, G., … & Stewart, G. B. (2020). Eight problems with literature reviews and how to fix them. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1-8.