Use of GPP3 for ethical guidance

April 1, 2021

Epidemiology designs for clinical trials

April 8, 2021In Brief

- The guidelines were established by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE).

- To investigate best practises and ethical principles in the conduct and reporting of research and other content presented in medical journals and assist publishers, editors, and those interested in peer review and biomedical publication in developing and disseminating reliable, transparent, reproducible, and impartial medical journal articles.

Introduction

These guidelines are specifically for writers who consider sending their work to one of the ICMJE’s members papers. Many non-ICMJE publications use these guidelines on their initiative. The ICMJE publication supports this practice, but it lacks the power to oversee or execute it. In both cases, authors may combine these guidelines with the guidance for authors provided by specific journals. The ICMJE supports the widespread distribution of these guidelines and full reuse of this document for educational and non-profit purposes without respect for copyright. However, all the recommendations and document can guide readers to www.icmje.org for the official, most recent edition. The ICMJE updates the recommendations regularly as new problems emerge.

This paper, formerly known as the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals, has been published in several editions by the ICMJE (URMs). The URM was created in 1978 to standardize manuscript publication support formatting and planning through journals. “Recommendations for Scholarly Work in Medical Journals: Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication”

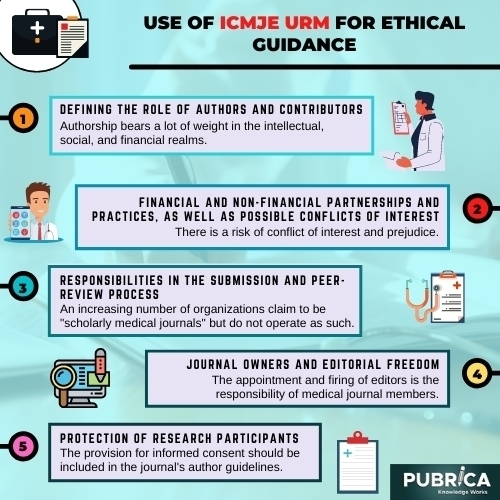

Use of ICMJE URM for ethical guidance

A. Defining the Role of Authors and Contributors

Authorship bears a lot of weight in the intellectual, social, and financial realms. Authorship also requires liability and transparency for work that has been written. The following suggestions are meant to ensure that contributors who have made significant intellectual contributions to a paper are given authorship credit. The contributors who are credited as authors are aware of their responsibilities and accountability for what is written. Since authorship does not specify what contributions qualify a person to be an author, some publications are now requesting and publishing information about each person’s contributions identified as a participant in a submitted report, at least for original research.

B. Financial and non-financial partnerships and practices, as well as possible conflicts of interest.

The transparency in which an author’s interactions and activities, specifically or topically relevant to work, are treated during the preparation, execution, publishing, peer review, editing, and publishing of scientific work affects a public interest in the scientific process quality of published medical publication support. A clinical opinion on a primary objective (such as patients’ health or the validity of research) is affected by a secondary interest. There is a risk of conflict of interest and prejudice (such as financial gain). Conflicts of interest beliefs are almost as important as actual conflicts of interest.

Financial links (such as jobs, consultancies, equity ownership or options, honoraria, trademarks, and paid expert testimony) are the easiest to spot, the ones that are more commonly viewed as possible conflicts of interest.

Those other interests, such as personal relationships or rivalries, academic rivalry, and intellectual values, can also reflect or be viewed as disputes.

C. Responsibilities in the Submission and Peer-Review Process

An increasing number of organizations claim to be “scholarly medical journals” but do not operate as such. These journals (also known as “predatory” or “pseudo-journals”) accept and print almost all submissions and charge article processing (or “publication”) fees, which are only disclosed to authors after a paper is accepted for publication. They sometimes tend to do peer review but do not, and they can have titles that are confusingly similar to well-known journals.

D. Journal Owners and Editorial Freedom

The appointment and firing of editors is the responsibility of medical journal members. Owners should provide editors with a contract that explicitly outlines their rights and liabilities, jurisdiction, the basic terms of their appointment, and dispute resolution mechanisms at the time of their appointment. The editor’s output can generally be measured using agreed-upon measures such as readership, manuscript submissions and handling times, and different journal metrics, among others.

E. Protection of Research Participants

Both inspectors can ensure that human research is prepared, performed, and documented in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration, as amended in 2013. All authors should request approval from an independent local, state, or national review body (e.g., ethics committee, institutional review board). The analysis was done in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration, the authors must clarify their reasoning and show that the study’s questionable aspects were accepted explicitly by a local, state, or national review authority.

The provision for informed consent should be included in the journal’s author guidelines. It should be stated in the written article where informed consent has been received.

Conclusion:

The ICMJE Recommendations have a limited ability to avoid market prejudice. Still, they provide helpful safeguards against the most severe possible commercial violations of literature, such as poor statistical requirements, guest authorship, and nondisclosure of industry participation. The Recommendations have since been used to develop research practices, such as study registration and evolving guidance on data sharing. The ICMJE must bear a particular responsibility for weaknesses in the content of medical literature, to the degree that these flaws are ignored or even promoted by the ICMJE’s criteria. By urging their continued evolution and asserting the validity of these flawed but necessary guidelines, beneficial effects on science and publishing standards, including in commercial literature. Avail Publication support services from Pubrica.

References:

1. Fugh-Berman, AJ. The haunting of medical journals: how ghostwriting sold “HRT”. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000335.

2. Matheson A. Corporate science and the husbandry of scientific and medical knowledge by the pharmaceutical industry. BioSocieties. 2008;3:355–82.

3. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4:e286.

4. Fugh-Berman A, McDonald CP, Bell AM, Bethards EC, Scialli AR. Promotional tone in reviews of menopausal hormone therapy after the Women’s Health Initiative: an analysis of published articles. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000425.