- Services

- Discovery & Intelligence Services

- Publication Support Services

- Sample Work

Publication Support Service

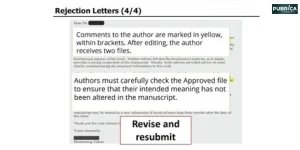

- Editing & Translation

-

Editing and Translation Services

- Sample Work

Editing and Translation Service

-

- Research Services

- Sample Work

Research Services

- Physician Writing

- Sample Work

Physician Writing Service

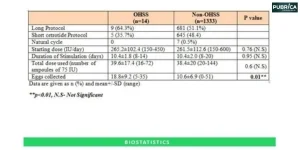

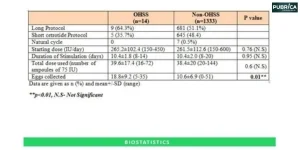

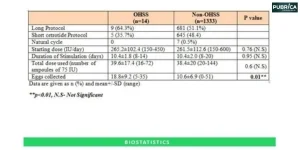

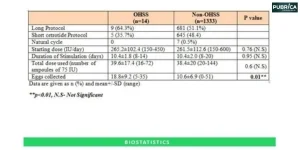

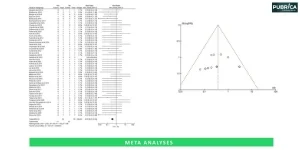

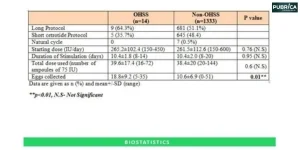

- Statistical Analyses

- Sample Work

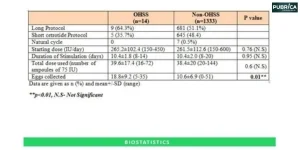

Statistical Analyses

- Data Collection

- AI and ML Services

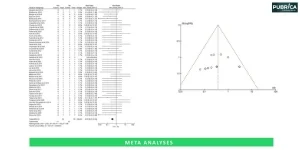

- Medical Writing

- Sample Work

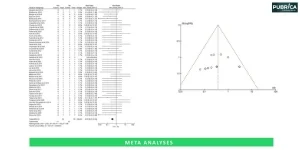

Medical Writing

- Research Impact

- Sample Work

Research Impact

- Medical & Scientific Communication

- Medico Legal Services

- Educational Content

- Industries

- Subjects

- About Us

- Academy

- Insights

- Get in Touch

- Services

- Discovery & Intelligence Services

- Publication Support Services

- Sample Work

Publication Support Service

- Editing & Translation

-

Editing and Translation Services

- Sample Work

Editing and Translation Service

-

- Research Services

- Sample Work

Research Services

- Physician Writing

- Sample Work

Physician Writing Service

- Statistical Analyses

- Sample Work

Statistical Analyses

- Data Collection

- AI and ML Services

- Medical Writing

- Sample Work

Medical Writing

- Research Impact

- Sample Work

Research Impact

- Medical & Scientific Communication

- Medico Legal Services

- Educational Content

- Industries

- Subjects

- About Us

- Academy

- Insights

- Get in Touch

- Services

- Discovery & Intelligence Services

- Publication Support Services

- Sample Work

Publication Support Service

- Editing & Translation

-

Editing and Translation Services

- Sample Work

Editing and Translation Service

-

- Research Services

- Sample Work

Research Services

- Physician Writing

- Sample Work

Physician Writing Service

- Statistical Analyses

- Sample Work

Statistical Analyses

- Data Collection

- AI and ML Services

- Medical Writing

- Sample Work

Medical Writing

- Research Impact

- Sample Work

Research Impact

- Medical & Scientific Communication

- Medico Legal Services

- Educational Content

- Industries

- Subjects

- About Us

- Academy

- Insights

- Get in Touch

PICO Framework in Evidence-Based Studies: A Complete Guide

With an ever-increasing body of knowledge, seeking critical evidence in the ocean of information is quite a challenge. Emerging contradictions further complicate decision-making in medical sciences, making the systematic approach necessary, such as (Evidence-based Medicine) EBM. EBM has developed into (Evidence-Based Practice) EBP and (Evidence-based Research) EBR, focusing on making clinical decisions using the latest research and guidelines. PICO, which is short for Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome, is a core element of EBM and EBP that simplifies the process of developing research questions [1]. Recent developments in PICO have expanded its usage to include complex components that make it more suitable for various evidence-based research. This article will discuss the recent advancements in PICO and its applications in evidence-based studies.

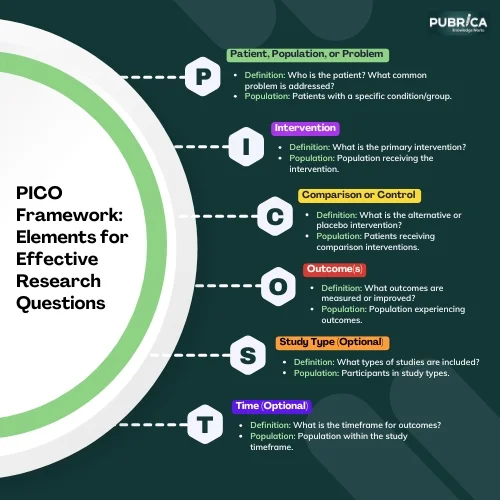

Key elements of PICO framework

The PICO framework was first introduced by Richardson et al. in 1995 as a widely used frame of reference in evidence-based research to measure the effectiveness of interventions. PICO stands for a mnemonic that directs the researcher in formulating a clinical research question and has variations such as PICOT and PICOS according to the context of the study. Here’s how these are applied:

The PICO framework offers a structured approach to formulating clinical questions, dividing them into four key components [1].

Table 1: PICO Framework Elements

| S. No | Elements | Definition | Population | Examples |

| 1 | P – Patient, Population, or Problem | Who is defined as a patient? What is the common problem, and what are the characteristics related to the population? | Patients with a specific condition or group | What is the effectiveness of Remdesivir for treating severe COVID-19 in adults compared with no/placebo treatment? |

| 2 | I – Intervention | What is the main intervention? | Population receiving the intervention | What is the effectiveness of low-dose aspirin in preterm delivery prevention in nulliparous women? |

| 3 | C – Comparison or Control | What is the major intervention of comparison or alternative intervention (if present)? | Patients receiving an alternative or placebo | Comparing Remdesivir treatment vs. no treatment; Comparing low-dose aspirin vs. placebo treatment for preterm delivery prevention. |

| 4 | O – Outcome(s) | What outcomes are anticipated to be achieved, assessed, measured, or improved? | Population experiencing the outcomes | Improved recovery rates from COVID-19, or reduction in the risk of preterm delivery. |

| 5 | S – Study Type (if applicable) | What types of studies or interventions are considered? | Participants in selected study types | Clinical trials examining the impact of Remdesivir or low-dose aspirin on the stated outcomes. |

| 6 | T – Time (if applicable) | What timeframe or duration is considered for the measurement/study? What is the required time to achieve the result of the intervention? | Timeframe relevant to the study/intervention | Time to recovery from severe COVID-19; Duration of intervention effectiveness in studies aimed at preventing premature birth. |

Application of PICO, PICOT, and PICOS:

PICO:

Designed for simple clinical questions, to be specific, define your population, intervention, comparison, and outcome. In this case, it is required to assess a new medication compared to the placebo within a particular population group. For instance, research studies that assess therapeutic ultrasound for knee osteoarthritis use PICO to compare ultrasound interventions with sham treatments and measure outcomes such as pain relief and functional improvement. Furthermore, it helps in designing research questions such as “Is intervention X more effective than intervention W for outcome Y in population Z?”

It can explore “In adults with type 2 diabetes (Population), does a ketogenic diet (Intervention) compared to a low-fat diet (Comparison) improve glycemic control (Outcome)?”.

PICOT:

This adds a timing element T-timeframe, useful for longitudinal studies or questions involving treatment duration. It is very commonly used in chronic condition research to determine long-term efficacy of treatments. For example, assessing the impact of a 6-month intervention versus a 3-month intervention on patient outcomes.

Question can frame using PICOT “Does the inclusion of only RCTs (Study type) impact the findings of dietary intervention outcomes in diabetes?”.

PICOS:

This contains the study design, which is very important for systematic reviews to include high-quality evidence. It is very helpful in meta-analyses to differentiate between RCTs and observational studies. For instance, meta-analyses that evaluate interventions for knee osteoarthritis often identify study designs such as randomized controlled trials to guarantee reliability and consistency in findings.

Example:

- Research Question: In children with asthma (P), how effective is a combination therapy (I) compared to inhaled corticosteroids alone (C) in reducing hospitalizations (O) based on randomized controlled trials (S)?

These types of frameworks help in the exact formulation of clinical research questions that facilitate more efficient literature searches and outcomes relevant to decisions made at the bedside. These frameworks are especially useful for formulating inquiries about prevention, prognosis, diagnostic precision, and treatment approaches.

PICO Framework: Quantitative VS Qualitative

The PICO framework, for Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Time, can be used with both qualitative and quantitative research to investigate the effectiveness of reciprocating instruments.

In the context of quantitative studies, it helps establish clinical and technical outcomes; for example, postoperative pain, reduction in microorganisms, or file breakage rates might be measured between reciprocating and rotary systems, over a specified time frame.

Example Research Question:

In patients undergoing root canal treatment (P), do reciprocating instruments (I) reduce postoperative pain (O) compared to rotary instruments (C)?

For qualitative studies, it may help guide any inquiries regarding the patient experience of OHRQoL after treatment or regarding clinician experiences with the tools [2]. Applying the PICOT framework in both methods helps to ensure organized evaluation of studies, exposing gaps and allowing the researchers to thoroughly synthesize evidence that guides future research.

Example Research Question:

“How do patients perceive their oral health-related quality of life after undergoing root canal treatment with reciprocating instruments compared to rotary instruments?”

A recently developed framework called AlpaPICO, which can be used to automatically extract PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome), significantly enhances the effectiveness of literature search in clinical research. This approach overcomes the limitations of labor-intensive manual processes in traditional systematic reviews using advanced natural language processing (NLP) techniques [3]. Further, it provides PICO elements extraction efficiently and accurately using Large Language Models (LLM).

Applying PICO in Evidence-Based Research

The PICO framework is crucial for evidence-based research, offering flexibility and clarity for various study designs, highlighting the importance of precise research questions in scientific investigations [1].

Step 1: Define the Research Question

Find a clinical or research problem based on observation, existing knowledge gaps, or clinical challenges [5].

Example:

Research Problem: Increasing incidence of Type 2 diabetes among young adults.

Research Question: “Does a Mediterranean diet have a better effect on glycemic control in young adults with Type 2 diabetes than a standard low-fat diet?

Step 2: Break Down the Question into PICO Elements

Take the research question and break it down into its basic elements:

- P (Population): The population of interest or the group being examined.

- I (Intervention): The primary treatment, procedure, or exposure under study.

- C (Comparison): The alternative intervention or standard treatment to compare with.

- (Outcome): The measurable effect or result of interest.

Example:

- P: Young adults with Type 2 diabetes.

- I: Mediterranean diet.

- C: Standard low-fat diet.

- O: Development in glycemic control (e.g., HbA1c levels).

Step 3: Literature Search

Create a systematic search strategy using PICO terms. Boolean operators and synonyms should be used to increase the accuracy of the search. Use major databases such as PubMed (MeSH Term), Cochrane Library, or Scopus.

Search Strategy Example

Search query: Create a search query using the combination of terms as below and use online library to extract the studies.

(Type 2 diabetes OR diabetes mellitus) AND (young adults OR adolescents) AND (Mediterranean diet) AND (low-fat diet) AND (glycemic control OR HbA1c levels)

Databases: Use the database like Mesh Term in PubMed, Cochrane Library, Scopus to search the literature related to studies, which further can filter only for RCTs (randomized controlled trials) or studies published in last 5 years

MeSH Term Search

Filters: only RCTs (randomized controlled trials) or studies published in the past 5 years.

Step 4: Analyze and Interpret Results

Use the selected studies to extract relevant data, evaluate the methodological quality, and synthesize the findings to answer the research question. Factors to consider include study design, sample size, and statistical significance.

Example:

Extracted Data:

- Study A: Mediterranean diet reduced HbA1c levels by 1.5% compared to a low-fat diet.

- Study B: Fasting blood glucose levels showed improvement, and patient adherence improved.

Synthesis:

There is consistent evidence that a Mediterranean diet is more effective than a standard low-fat diet in improving glycemic control in young adults with Type 2 diabetes.

Conclusion

The PICO framework remains a very foundational tool for evidence-based studies, providing clarity and direction in clinical research. However, the evolving nature of the challenges in healthcare requires changing the approach to be incorporated with technology for complex questions. Researchers and clinicians must be alert to new approaches and innovations, for example, AI-driven tools, and the expansion of frameworks to ensure that the evidence-based practice continues.

References

- Hosseini, M.S., Jahanshahlou, F., Akbarzadeh, M.A., Zarei, M. and Vaez-Gharamaleki, Y., 2024. Formulating research questions for evidence-based studies. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 2, p.100046.

- Immich, F., de Araújo, L.P., da Gama, R.R., da Rosa, W.L.D.O., Piva, E. and Rossi‐Fedele, G. (2024) Fifteen years of engine‐driven nickel–titanium reciprocating instruments, what do we know so far? An umbrella review. Australian Endodontic Journal, 50(2), pp.409-463.

- Ghosh, M., Mukherjee, S., Ganguly, A., Basuchowdhuri, P., Naskar, S.K. and Ganguly, D. (2024). AlpaPICO: Extraction of PICO frames from clinical trial documents using LLMs. Methods, 226, pp.78-88.

- Waldrop, J. and Jennings-Dunlap, J. (2024) CE: Beyond PICO—A New Question Simplifies the Search for Evidence. AJN The American Journal of Nursing, 124(3), pp.34-37.

- Feldner, K. and Dutka, P. (2024) Exploring the Evidence: Generating a Research Question: Using the PICOT Framework for Clinical Inquiry. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 51(4), pp.393-395.

Give yourself the academic edge today

Each order includes

- On-time delivery or your money back

- A fully qualified writer in your subject

- In-depth proofreading by our Quality Control Team

- 100% confidentiality, the work is never re-sold or published

- Standard 7-day amendment period

- A paper written to the standard ordered

- A detailed plagiarism report

- A comprehensive quality report