What are the different sources of data used to extract for writing a systematic review

May 26, 2021

How many patients does case series should have? In comparison to case reports

June 2, 2021Introduction

A systematic analysis seeks to gather data to address a specific study issue. This entails locating all primary research related to the specified review issue, critically evaluating the research, and synthesizing the results. Systematic analyses may draw together various forms of information to analyze or clarify the context. They may incorporate results from different scientific trials to create a new integrated finding or inference. Any study topic can be addressed using systematic reviews. Curiosity in a subject and a need to address a particular question can motivate a systematic analysis.The question should define the specific demographic to which the question refers and any action and concern results. A well-defined study issue will aid in the clarification of the eligibility criterion for the inclusion of related studies (and exclusion of irrelevant studies). For comparatively straightforward systematic reviews of intervention efficacy, the “PICO” paradigm is often used to inform the systematic review topic (1). The PICO method for framing systematic review study questions is explained in this article.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) involves incorporating professional practice, the best available scientific data, and the patient’s principles and interests into clinical decision-making. The steps in practicing EBM are based on the patient. They include posing well-focused questions, looking for the best possible data, assessing the relevance of that evidence, and then adapting the findings to the patient’s treatment. Universal access to healthcare information and knowledge-based resources is needed to sustain 21st-century health care and EBM practice. To address scientific questions, clinicians and educators now use various tools and interfaces to scan the biomedical literature. According to the literature, often clinical inquiries go unanswered because of difficulty formulating a specific topic, forgetting the issue, a lack of access to knowledge services, and a lack of search skills(2).

The first and arguably most critical move in the EBM process is to formulate a well-focused topic. It can be challenging and time-consuming to find adequate tools and look for valid information without a well-focused query. EBM practitioners often use a specialized system known as PICO to shape the query and promote the literature review. Patient Problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome is an abbreviation for PICO. The PICO concept can be extended to PICOTT by including details about the kind of question being posed (therapy, diagnosis, prognosis, damage, and so on) and the best kind of research design for that specific question. Using this approach assists the clinician in articulating the core parts of the therapeutic query that are most relevant to the patient and supports the evaluation process by defining the key principles for an appropriate search strategy(3).

PICO Strategy to Frame the Research Question

Successful search methods are usually well-structured and based on a PICO architecture. Population Intervention Comparison Outcome (PICO) systems assist the searcher in categorizing search words. Since the medical model of study would usually be identified by; a target demographic, for example, children; an intervention, for example, an exercise regime; the form of comparison, for example, a randomized control trial; and effect, for example, weight control, PICO is very good at recognizing medical literature where systematic analysis is popular. A well-constructed study query should include four components. The PICO model is a useful method for grouping and narrowing down a study issue into a searchable query, and dividing the PICO components aids in the identification of search terms/concepts to use in literature searches.

P ‑ Patient, problem, population

I ‑ Intervention, prognostic factor, exposure

C ‑ Comparison

O ‑ Outcome

The PICO strategy results in a well-constructed test topic, which leads to a study design that yields the highest degree of proof (4).

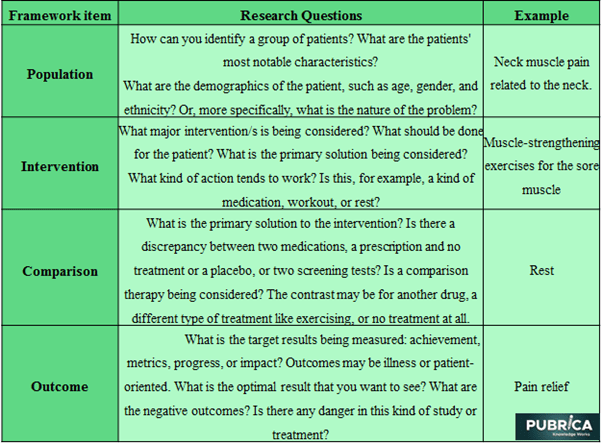

PICO Framework

Finding appropriate resources and useful facts without a well-focused query can be difficult and time-consuming (5).

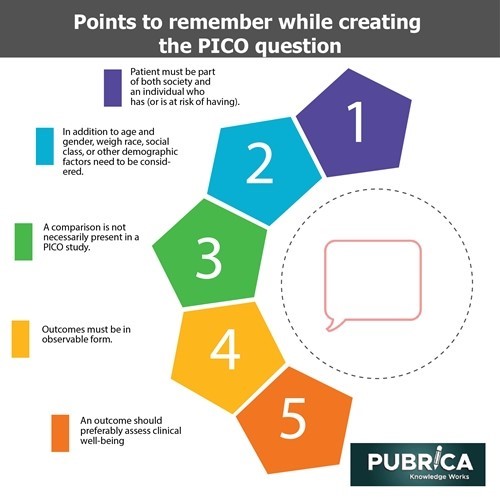

Keep the following points in mind when creating the PICO question:

- Your patient is both a part of a society and an individual who has (or is at risk of having). As a result, in addition to age and gender, you can need to weigh race, social class, or other demographic factors.

- A comparison is not necessarily present in a PICO study.

- The best proof comes from rigorous trials of statistically meaningful results, but outcomes can be observable (6).

- An outcome should preferably assess clinical well-being or quality of life rather than alternatives such as experimental test outcomes.

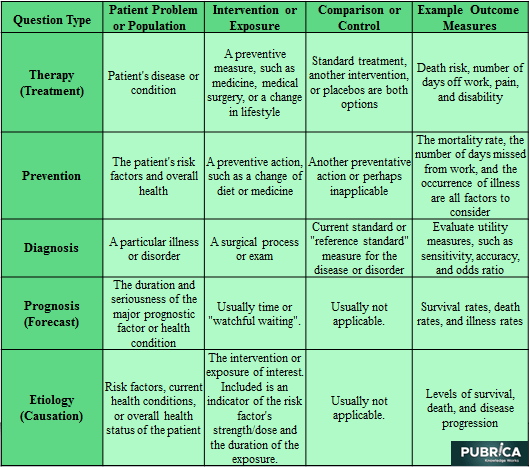

PICO Elements as perDomain

When developing your question using the PICO system, consider the sort of question you are posing (therapy, prevention, diagnosis, prognosis, etiology). The table below shows how Problems, Interventions, Comparisons, and Outcomes differ depending on your question’s type (domain) (7).

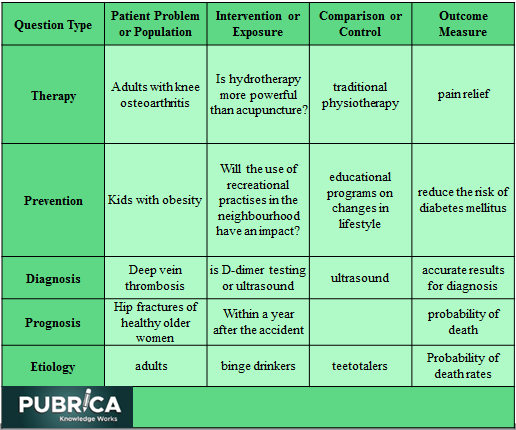

Creating a Question Statement

It is simple to compose your question statement after clearly defining your question’s key elements using the PICO system. Any illustrations are given in the table below (8).

Conclusion

These structures are instruments for guiding the creation of a search strategy. A slight modification to the medical query structures, usually as basic as moving patient to population, allows structuring questions from both library and information science fields. Rather than considering any of these systems to be fundamentally different, consider the following elements: timeline, length, background, (health care) setting, atmosphere, type of issue, type of study nature, practitioners, visibility, outcomes, stakeholders, and scenario. Where required, these can be used interchangeably. Maintaining an understanding of the various possibilities for structuring searches broadens the frameworks’ future uses. A thorough understanding of the structures also allows the searcher to tailor tactics to each situation rather than adapt a search situation to a system (9).

References:

[1]Waclawovsky G, Pedralli ML, Eibel B, Schaun MI, Lehnen AM. Effects of Different Types of Exercise Training on Endothelial Function in Prehypertensive and Hypertensive Individuals: A Systematic Review. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2021;116(5):938-47.

[2] Kloda, L. A., Boruff, J. T., &Cavalcante, A. S. (2020). A comparison of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) to a new, alternative clinical question framework for search skills, search results, and self-efficacy: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA, 108(2), 185–194.

[3] Miller, V., Hamler, T., Beltran, S., & Burns, J. (2020). The Social Worker in the Nursing Home: A Systematic Review of the Literature from 2010 to 2020. Innovation in Aging, 4(Suppl 1), 960.

[4] Milde, AM, Gramm, HB, Paaske, I, Kleiven, PG, Christiansen, Ø, SkaaleHavnen, KJ. Suicidality among children and youth in Nordic child welfare services: A systematic review. Child & Family Social Work. 2021; 1– 12.

[5] Alex Pollock and Eivind Berge, How to do a systematic review, International Journal of Stroke

2018, Vol. 13(2) 138–156. DOI: 10.1177/1747493017743796.

[6]Palaskar JN. Framing the research question using PICO strategy. J Dent Allied Sci 2017;6:55.

[7] Schardt, C., Adams, M. B., Owens, T., Keitz, S., &Fontelo, P. (2007). Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 7, 16. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-7-1.

[8] Fineout-Overholt, E., & Johnston, L. (2005). Teaching EBP: asking searchable, answerable clinical questions. Worldviews On Evidence-Based Nursing, 2, 157-160.