What is the Bayesian random-effects meta-analysis model for normal data

May 26, 2021

The PICO framework for framing systematic review research questions

May 28, 2021In Brief

Systematic reviews have studied rather than reports as the unit of interest. So,many reports of the same study need to be identified and linked together before or after data extraction.Because of the growing abundance of data sources (e.g., studies registers, regulatory records, and clinical research reports), review authors can determine which sources can include the most relevant details for the review and provide a strategy in place to address contradictions if evidence were inconsistent throughout sources(1).

Introduction

Systematic analyses seek to find all important trials to their study issue and synthesise information about the design, risk of bias, and outcomes of those studies. As a result, a systematic study is heavily dependent on interpreting and analysing evidence from these analyses. For systematic analyses, data collected should be reliable, complete, and available for future updating and data sharing. The methods used to make these choices must be straightforward, and they should be selected with prejudgments and human error in mind (2).We define data collection methods used in systematic reviews, including data extraction directly from journal articles and other case study reports.

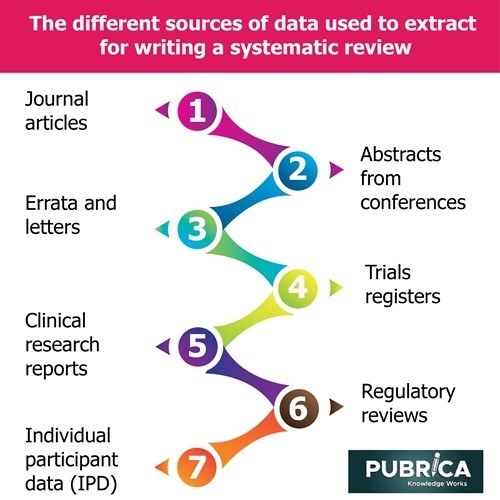

Different Sources of data

- Journal articles are the bulk of data in systematic reviews that comes from this source. It’s worth noting that a thesis can be published in many journal papers, each reporting on a different part of the research (e.g. design, main results, and other results).

- Abstracts from conferences are widely accessible. On the other hand, conferencing abstracts are extremely subjective in terms of efficiency, precision, and level of description.

- Errata and letters will provide valuable knowledge about experiments, such as critical flaws and retractions, and research reviewers can investigate them where they are found (3).

- Trials registers keep track of studies that have been designed or begun. They’ve become a valuable resource for locating experiments, matching reported outcomes and effects to those expected, and collecting feasibility and safety evidence that isn’t readily accessible elsewhere.

- Clinical research reports (CSRs) are unabridged and concise accounts of the clinical challenge, nature, behaviour, and outcomes of clinical trials that meet the International Conference on Harmonisation’s format and content guidelines (ICH). Pharmaceutical firms apply CSRs and other required documents to regulatory authorities to secure marketing clearance for medications and biologics for a particular indication.

- Regulatory reviews, such as those obtainable from the US Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency, may offer invaluable information about drug, biologic, and medical product trials applied for marketing approval by manufacturers. These papers are summaries of CSRs and associated documents prepared by agency personnel as part of authorising goods for sale after a reanalysis of the initial trial results.

- Individual participant data (IPD) is normally requested directly from the study’s researchers, or it can be found in open data repositories. Variables that reflect each participant’s profile, intervention (or exposure) population, prognostic factors, and outcome metrics are usually included in these data (4).

Data Extraction Tools

- Excel

Excel is the essential device for managing the screening and information extraction phases of the systematic review measure. We can design customised workbooks and spreadsheets for systematic review. A further developed way to utilise Excel for this object is the PIECES approach, planned by a librarian at Texas A&M.

- Covidence

Covidence is software built explicitly for dealing with each progression of a systematic review project, including data extraction.

- RevMan

RevMan is free software used to oversee Cochrane surveys. For more data on RevMan, including clarifying how it could be utilised to extricate and examine information.

- SRDR

SRDR (Systematic Review Data Repository) is a Web-based tool for extracting and managing data for systematic review. It is additionally an open and accessible document of a systematic review and their information.

- DistillerSR

DistillerSR is a systematic review management program. It guides the reviewer in making project-explicit structures, separating, and examining information (5)

Conclusion

A systematic review article is not conceivable without a decent literature search. The writing search has its principles that, for the most part, apply to both unique and review examines. A detailed review includes a literature search method guided by keeping an accurate and straightforward record of the whole cycle. It is valuable to outline an Excel table where the choice measures will record references of studies. This will assist the reviewer with understanding the methodology, and the outcomes got. If any inquiries ought to emerge, this proof will make it simple to discredit and clarify any doubts about the cycle or the outcomes (6).

References

- Jackson, Tanya, et al. “Classification of aerosol-generating procedures: a rapid systematic review.” BMJ open respiratory research 7.1 (2020): e000730.

- Spasic, Irena, and Goran Nenadic. “Clinical text data in machine learning: Systematic review.” JMIR medical informatics 8.3 (2020): e17984.

- Tamiminia, Haifa, et al. “Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: A meta-analysis and systematic review.” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 164 (2020): 152-170.

- Büchter, Roland Brian, Alina Weise, and Dawid Pieper. “Development, testing and use of data extraction forms in systematic reviews: a review of methodological guidance.” BMC medical research methodology 20.1 (2020): 1-14.

- Hu, Ruiqi, Michelle Helena van Velthoven, and Edward Meinert. “Perspectives of people who are overweight and obese on using wearable technology for weight management: systematic review.” JMIR mHealth and uHealth 8.1 (2020): e12651.

- Mengist, Wondimagegn, TeshomeSoromessa, and GudinaLegese. “Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research.” MethodsX 7 (2020): 100777.