How to Finalize MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms – Guidelines for Searching Articles

August 23, 2021

How to deal with improper or unethical peer review

September 8, 2021In brief

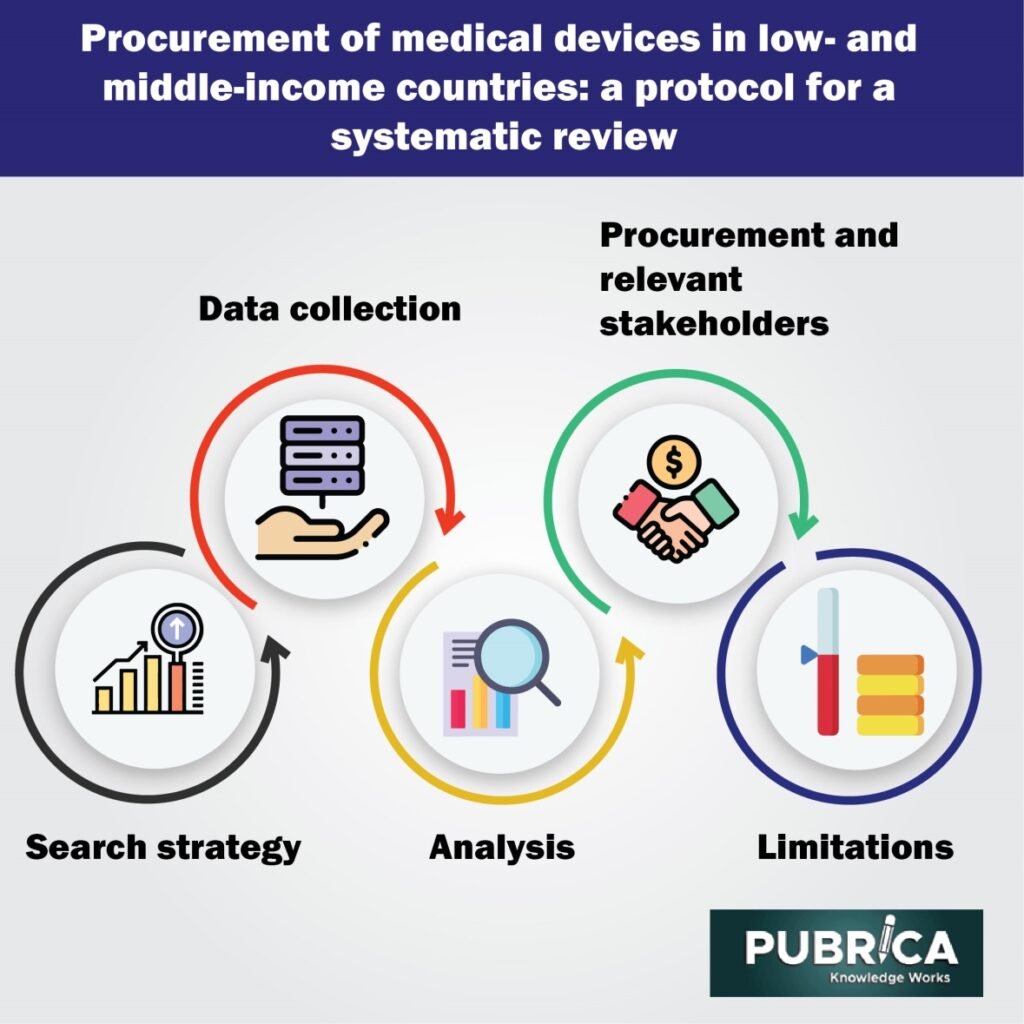

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) medical device procurement processes are poorly understood and researched. International public health organisations and research agencies publish a wide body of mostly grey literature, including guidelines, manuals, and recommendations, to aid LMIC policy formulation in this area. This part of conducting a systematic analysis to classify and investigate the medical device procurement methodologies proposed and other literature (1). The facilitators and obstacles to procurement will be established, and methodologies for prioritising medical devices under resource constraints will be discussed.

Introduction

Medical devices and equipment are important for providing high-quality health care. In low- and middle-income nations, reports and studies point to a shortage of basic medical devices and medical equipment that has fallen out of use. It has a significant impact on healthcare delivery and also results in a loss of staff and funds. There are two potential causes for this issue, according to the WHO’s Priority Medical Devices project. First, medical device manufacturers seek out economies in high-income countries because of the higher profit margins. As a result, medical device supply and equipment design are limited to products and requirements appropriate for implementation in environments with specialised facilities and technologically skilled human resources. Second, low- and middle-income countries face judicious medical device procurement (LMICs) (2).

Table: 1 Procurement of medical devices at national level concerning country income classification

| Country classification | Does procurement of medical devices occur at the national level? | |

| Yes | NO | |

| Low income | 25 | 8 |

| Low-middle income | 31 | 7 |

| Upper-middle income | 30 | 17 |

| High income | 17 | 27 |

| Total | 103 | 59 |

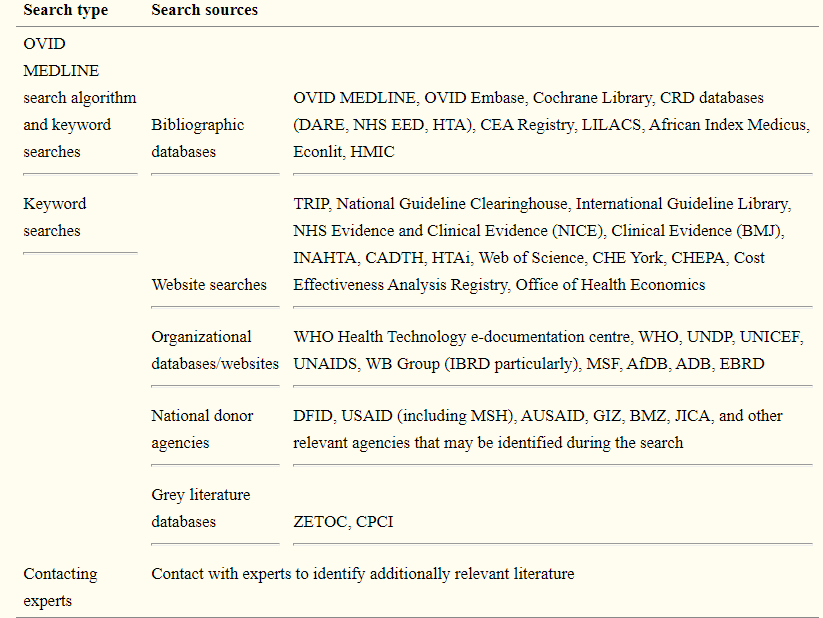

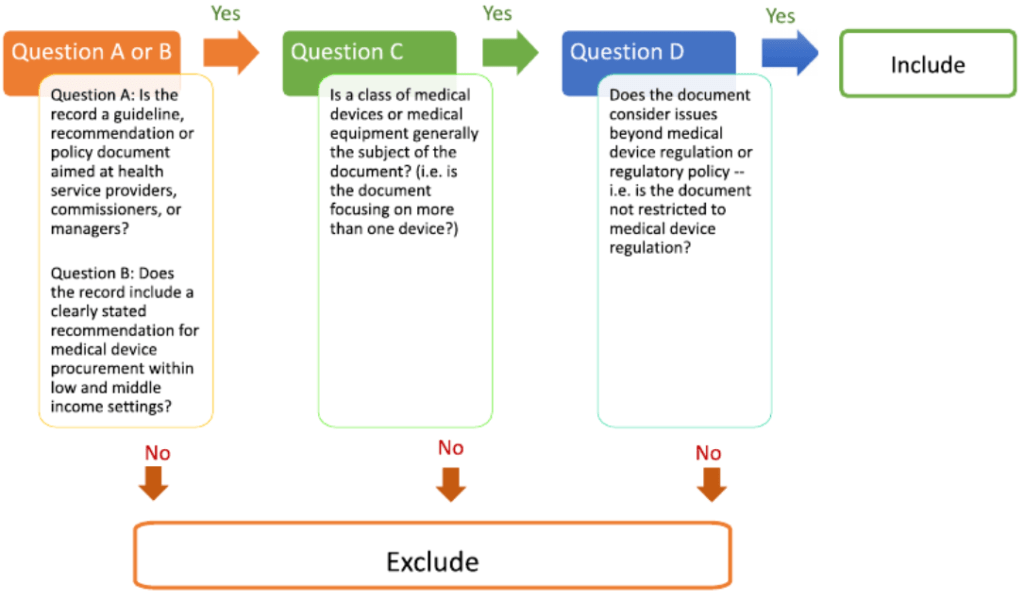

Search strategy

Early scoping searches on medical device procurement strategies for LMICs turned up much grey literature from foreign public health agencies, think tanks, and other organisations, but few journal articles or research studies. As a result, it was critical to creating search and selection strategies that were as broad and inclusive as possible, with no time or language limitations. However, the collection of data documents to be included will be limited to publicly accessible digitised content, partly due to resource limitations and partly because we believe this best reflects the different materials that LMICs will have access to. A filled list of sources to be searched is provided in the Table.

Data collection

One reviewer (KD or MB) extracted data from all included documents based on a pre-determined list of questions. Normative or descriptive accounts of MDE procurement and technology management processes; the relevance of health technology assessment exercises and health needs assessments in procurement; the input of health care professionals or specialist staff (e.g. biomedical engineers, economists) in procurement decisions; device installation, maintenance, and decommissioning procedures. Now looked for clear accounts of MDE prioritisation processes in the documentation and extracted quotes or process details for qualitative review (3).

Analysis

To summarise and analyse the data collected, two methods of analysis were used. For issues related to the research questions raised, narrative synthesis provided a summative and descriptive report of all included documents. For a subset of documents detailing concrete prioritisation methods/processes, a qualitative meta-summary was used to investigate MDE prioritisation.

Procurement and relevant stakeholders

Individual health facilities also participate in the direct acquisition. Not all medical device procurement decisions are taken at the regional, country, or supra-national level. The authors of the documents reviewed caution that such procedures are not uniform across LMICs: hospitals also lack dedicated resources for MDE procurement and rely on donations, reuse, and recycling to meet technical needs.

The literature search help is largely vague on how stakeholder views are aggregated or divergent opinions treated, with only three documents containing examples of such accounts. The value of multi-criteria decision-making approaches for aggregating and integrating individual decision-makers perspectives. Decision-makers involved in the procurement of MDEs and clinical or financial administration personnel use this approach to rate technologies based on a specific and well-defined set of parameters, such as patient population benefit. After that, the highest-scoring inventions are purchased (4). However, such mechanisms can be inherently biased: decision-makers experiences may not represent the best available evidence globally.

Limitations

Distinguish that the current project has several limitations. To begin, recognise the challenge of conducting a first-line analysis on a subject with methodologically diverse literature. Second, we do not attempt to find or include national policy documents on medical devices in this review.

Future scope

Furthermore, the scope of the analysis may be restricted, as it is not intended to define and include prioritisation methodologies for whole intervention packages rather than individual devices or equipment. To ensure that relevant methodologies are not overlooked, reviewers will consult international health experts to recognise any relevant methodologies and discuss the current review’s results in light of them (5).

Conclusion

It’s unclear how LMICs go about procuring and prioritising medical devices. Internationally proposed guidelines, recommendations, or reports are regularly provided to advise LMICs on this subject, whether produced by public health agencies or clinical research organisations. They may affect their national policy formulation. This systematic review aims to describe these methodologies, investigate the factors that have been identified to influence procurement practises in LMICs, and develop a preliminary framework for how medical device prioritisation and procurement can be planned and conceived in resource-constrained settings. The results of this systematic review help will formulate initial hypotheses about what factors and stakeholders influence these processes and a quality assurance structure capable of providing LMIC decision-makers with a well-rounded understanding of the topic(6).

References

- Anderson, Darcy M., et al. “Safe healthcare facilities: a systematic review on the costs of establishing and maintaining environmental health in facilities in low-and middle-income countries.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18.2 (2021): 817.

- Torloni, Maria Regina, et al. “Quality of medicines for life-threatening pregnancy complications in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review.” PloS one 15.7 (2020): e0236060.

- Singh, Neha S., et al. “A realist review to assess for whom, under what conditions and how pay for performance programmes work in low-and middle-income countries.” Social Science & Medicine (2020): 113624.

- Roberson, Jeffrey L., et al. “Lessons Learned From Implementation and Management of Skin Allograft Banking Programs in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Burn Care & Research 41.6 (2020): 1271-1278.

- Gravitt, Patti E., et al. “Achieving equity in cervical cancer screening in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs): Strengthening health systems using a systems thinking approach.” Preventive medicine 144 (2021): 106322.

Ryan, Nessa, et al. “Implementation outcomes of policy and programme innovations to prevent obstetric haemorrhage in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review.” Health Policy and Planning 35.9 (2020): 1208-1227.