How to carry on multiple projects in medical writing?

March 12, 2021

Benefits of copyediting in manuscript writing

March 22, 2021In Brief

A scientist’s routine involves scientific correspondence. Scientists are supposed to give lectures, write articles and ideas, communicate with a broad spectrum of audiences, and inform others. As a result, scientists must learn to collaborate to be successful, regardless of their profession or career path. Furthermore, scientists must develop strong medical communication service skills. To put it another way, to be a good scientist, he must be an effective communicator.

Introduction

Science contact isn’t a brand-new idea. Scientists in the United Kingdom have been communicating their scientific discoveries to the public since at least the early nineteenth century when scientists like Michael Faraday spent time in the public dates and a vast amount of time and effort into popularizing Science. However, science communication as a scholarly discipline is a comparatively recent field, having progressed through three big stages in the United Kingdom: scientific literacy, public awareness, and civic participation. Public Understanding of Science (PUS) and Public Science and Technology Engagement (PEST).

As a result of going through these three phases, science communication ideology has changed from a predominantly deficit paradigm (in which scientists seek to ‘fill’ holes in the public’s knowledge) to one that promotes two-way interaction between scientists and the public. Mainly non -experts ( the general public and scientists from other fields) and specialists (specialist scientists) in different fields by the medical marketing services.

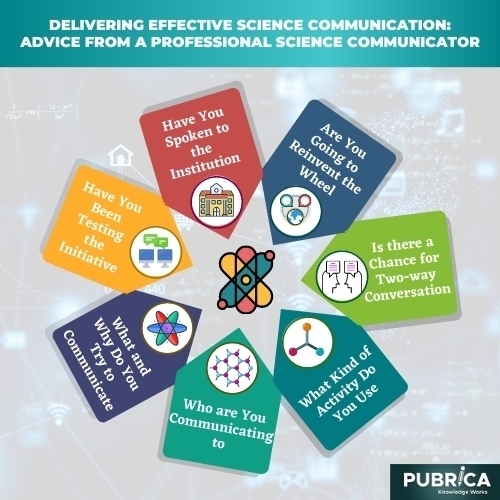

Practical advice from a professional science communicator

In the special issue’s editorial (and elsewhere, e.g., embedding science communication practices within a project with a specific long-term goal or vision is a successful way to build traction and effect. It can have a range of advantages, including resource re-use, interdisciplinary cooperation, and a greater probability that the initiative(s) can support practising scientists in their careers and progress in medical communications companies.

1. What and why do you try to communicate?

When it comes to improving scientific education initiatives, these are the two most important questions to consider. You may have a good idea of what you want to do. the subject you want to talk about, but what is your goal, and how can you achieve it? Where do you find healthy, meaningful communication? For example, you may want to produce a science communication project that looks at famous female scientists’ scientific successes to encourage female scientists’ next generation.

2. Who are you communicating to?

It’s essential to think of who the audience is, so the form of operation (see below), the purpose for interacting, and the vocabulary used will vary significantly between various classes and between individuals. Medical Communication experts, the relevance of antimicrobial tolerance to a community of schoolchildren would necessitate a different strategy than communicating the same issue to nurses at a nearby hospital.

3. What kind of activity do you use?

There are various forms of science communication practices, categorized into three categories: conventional journalism (e.g., newspapers and radio), life or face-to-face meetings, and online science communication, For example, community seminars, panel discussions, and science festivals and multimedia exchanges (Blogs, websites, photographs, and podcasts). This article is primarily about face-to-face sessions.

4. Is there a chance for a two-way conversation?

It’s all too easy to build a science communication experience to provide a particular piece of knowledge or bring an audience’s visibility. However, such an agreement isn’t realistic. No matter how engaging a solution is, it can never be considered natural—communication in all ways. Two-way collaboration ensures that the scientists in charge of the activities are listening to and learning about the people with whom they are interactive, like medical communications agency.

5. Are you going to reinvent the wheel?

It’s a brilliant idea to check on the internet or inquire in your area to see if someone else has done or is planning to do something close to your operation. Collaborating, or at the very least being collaborative. Being mindful of what has come before will help to speed up the process of being more successful. Delivery by reducing the amount of time spent on production and assisting you in avoiding costly mistakes and avoiding future traps, and helping you draw on your achievements on others’ experiences. Using existing materials saves time and money, which can be best used on other tools or a more efficient appraisal approach in healthcare communication services.

6. Have you spoken to the institution?

The public engagement/widening participation/school outreach team at your institute is an excellent first point when implementing any science communication program. On an institute-by-institute basis, the team’s title and position can vary. They are an invaluable resource for getting feedback on your proposals and finding volunteers.

7. Have you been testing the initiative?

It is also helpful to beta-test any proposed events or programs as part of creating science communication initiatives. Scientific communication services have a strategy that guarantees that all technical problems are ironed out (picture or video synchronization with the video equipment to be used).

It also puts any interested scientists at ease and prepares them for when the event goes live. It’s usually a good idea to enlist postgraduate and undergraduate students’ assistance during the beta-testing process.

Conclusion:

Successful science communication services can be a time-consuming and resource-draining activity, particularly if you’re learning a new skill set on top of your other academic obligations. It is, though, a challenging task. The rewarding and fun pursuit that can aid in the development of skills that are currently lacking. Communication and networking are helpful in other fields of academia. The best advice is to consider working with other professional science communicators and social scientists. These people will be aware of any new research and best practice in the field of science communication.

References:

[1] L. Bowater, K. Yeoman, Science communication: a practical guide for scientists, John Wiley & Sons2012.

[2] M.W. Bauer, The evolution of the public understanding of Science – discourse and comparative evidence, Science, technology and society 14(2) (2009) 221-240.

[3] S. Illingworth, J. Redfern, S. Millington, S. Gray, What’s in a Name? Exploring the Nomenclature of Science Communication in the UK [version 2; referees: 3 approved, one approved with reservations], 2015.

[4] A. Prokop, S. Illingworth, Not Communicating Science? Aiming for national impact [version 1; referees: 1 approved with reservations, two not approved], 2016.