Making Sense of Effect Size in Meta-Analysis based for Medical Research

June 14, 2021

Statistical analyses of case-control studies

June 23, 2021In brief

For various illnesses, such as asthma, heart failure, and diabetes, evidence-based health care approaches are accessible. Patient safety research has traditionally focused on data analytics to identify patient safety issues and show that a new practice will improve quality and patient safety. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is widely recognised as a central component of healthcare professional education worldwide. However, competence in this field is difficult, as seen by the differences between “best EBP” and actual clinical care. Translation science is a promising field of research that is fast expanding. Even though numerous healthcare practises have an evidence-based to guide care delivery, they are not routinely used (1).

Introduction

EBP comes in a variety of forms and has been utilised in a range of clinical contexts. Selection of a practise topic (e.g., discharge instructions for individuals with heart failure), critique and syntheses of evidence, implementation, and evaluation of the impact on patient care and provider performance, as well as consideration of the context/setting in which the practice is implemented are all common elements of these models. The learning that occurs during translating research into practice is important to capture and feedback into the process to alter the evidence-based guideline and the implementation strategies (2).

Steps of Evidence-Based Practice on health communication

People who conduct research or develop knowledge, those who use evidence-based information in practice, and those who serve as boundary spanners to connect knowledge generators with knowledge users can all contribute to the adoption of EBPs.

The three major steps of knowledge transfer are 1) knowledge generation and distillation, 2) diffusion and dissemination, and 3) organisational adoption and execution. These steps of knowledge transfer are viewed through the eyes of new knowledge creators/researchers, and they begin with choosing which discoveries from the patient safety portfolio or particular research initiatives should be communicated.

Knowledge creation and distillation involve conducting research (with expected variations in readiness for use in healthcare delivery systems) and then packaging relevant research findings into actionable products—such as specific practise recommendations—to increase the probability that research evidence will be used in practice. For research findings to be applied in care delivery, the knowledge distillation process must be informed and guided by end-users.

Diffusion and dissemination: It entails collaborating with experts and healthcare institutions to distribute knowledge that may be used as a foundation for action (e.g., necessary discharge education for hospitalised patients with heart failure). Dissemination collaborations bring together academics and mediators who can operate as knowledge brokers and connectors between practitioners and healthcare delivery organisations. Multifaceted dissemination techniques must be used in targeted dissemination efforts, focusing on channels and media that are most effective for certain user segments (e.g., nurses, physicians, pharmacists).

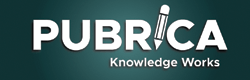

End-user adoption, implementation, and institutionalisation: This is the last step in the knowledge transmission process. This stage aims to get companies, teams, and people to accept and implement evidence-based research findings and innovations in their daily practices. The EBP topic (e.g., medication error reduction), organisational social system characteristics (such as operational structures and values, the external health care environment), and individual clinicians all have complex interrelationships when it comes to implementing and maintaining EBPs in health care settings(3).

Translation science

The study of strategies and variables that impact individual and organisational adoption of EBPs to improve clinical and operational decision-making in health care is known as translation science. This includes evaluating the impact of interventions on encouraging and maintaining EBP adoption. Describe facilitators and barriers to information absorption and usage, organisational determinants of adherence to EBP standards, attitudes toward EBPs, and define the structure of the scientific field are all examples of translation studies.

A conceptual model that organises the strategies being tested elucidates the extraneous variables (e.g., behaviours and facilitators) that may influence EBP adoption (e.g., organisational size, user characteristics) and builds a scientific knowledge base for this field of inquiry is required for translation science (4).

Figure 1: translation research science model

The practical implication from translation science

Principles of Evidence-based practice for patient study

Some translation science principles are informative for implementing patient safety initiatives (5):

- First, assess the context and involve point-of-care health care staff in selecting and prioritising patient safety initiatives, explicitly articulating the evidence base (strength and kind) for the enduring safety practice topic(s) and the conditions or situation to which it applies. These announcement messages must be carefully created and personalised to the needs of each stakeholder user group.

- Second, demonstrate why the organisation and individuals within the organisation should commit to an evidence-based safety practice subject using qualitative or quantitative data (e.g., near misses, sentinel incidents, adverse events, and injuries from adverse events). In contrast to administrators who argue, “We must do this because it is an external regulatory mandate,” clinicians are more engaged in embracing patient safety efforts when they understand the evidence base of the practice.

- Third, didactic education alone will never be sufficient to influence behaviour; one-time training on a specific safety programme will not be enough. Improved knowledge may not always imply improved performance. Organisations must instead invest in the resources and skills needed to foster a culture of evidence-based patient safety procedures, where inquiries are encouraged, and procedures are put in place to make doing the right thing simple.

- Fourth, the context of EBP patient safety improvements must be addressed at every stage of the application process; piloting the change in practice is critical to determining the fit between EBP patient safety information/innovation and the care delivery setting.

- Finally, it’s critical to assess the implementation process and outcomes. Users and stakeholders must be assured that efforts to increase patient safety greatly influence care quality. Suppose a new barcoding system is being used to administer blood products, for example. In that case, it’s critical to verify that the stages in the process are being monitored (process displays) and that the change in practice is reducing blood product transfusion errors (outcome indicators).

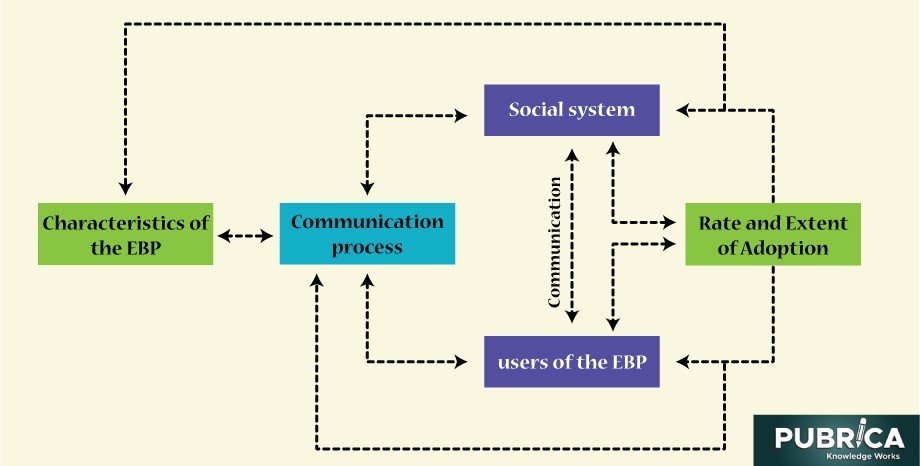

Table 1: Examples of Implementation Strategies for each Component of the Translation Research science Model

Evidence-based practice education for patient and healthcare professions

Expert interviews with EBP experts were performed to obtain up-to-date and nuanced information about EBP education from a global viewpoint. Experts from the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia were invited to participate through email based on their contributions to peer-reviewed research and recognised innovation in EBP education.

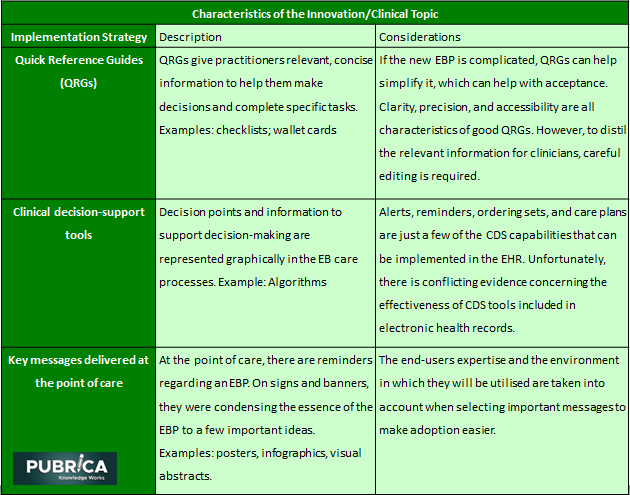

Three main classifications emerged, namely (1) ‘EBP curriculum considerations’, (2) ‘Teaching EBP’ and (3) ‘Stakeholder engagement in EBP education. The overriding subject of ‘Improving healthcare through increased education and application of EBP’ was informed by these categories (6).

Figure 2: Summary of data analysis findings from evidence-based practise (EBP) expert interviews—theme, categories and subcategories.

EBP curriculum considerations

With clear importance on the necessity for EBP principles to be integrated throughout all healthcare professions curricula, definitive advice regarding curriculum considerations was provided. Educators must ‘draw out evidence-based components’ from any curricular content areas, including its implementation into assessments and examinations, regardless of teaching context. The incorporation of EBP into the clinical curriculum, in particular, was deemed critical to optimal learning and practice outcomes. If students see an opposition between EBP and actual clinical care, “never the twain shall meet,” necessitating integration in such a way that it is “seen as part of the fundamentals of optimum clinical care.” The fact that EBP is a basic component of the professional curriculum and is linked to professional accreditation processes emphasises the importance of teaching EBP.

Teaching EBP

It was emphasised that effective techniques and practical procedures be used to achieve successful student learning and understanding. The clinical relevance of the teaching strategy and accompanying methodologies and student exposure to EBP facilitated dynamically and excitingly were particularly significant. One of the most effective training strategies was consistently stated as utilising patient examples and clinical scenarios.

Stakeholder engagement in EBP education

The involvement of national policymakers, healthcare experts, and patients in EBP was thought to have a lot of promise for improving its teaching and clinical use. The lack of a unified government and national strategy on EBP teaching has been identified as a hindrance to the plan’s implementation, resulting in a somewhat “ad-hoc” approach, reliant on specific educational or research institutions.

Conclusion

Although the science of interpreting research into practice is still in its early stages, some evidence suggests which implementation techniques should promote patient safety. However, there is no magic bullet for putting study findings into reality. Several strategies may be required to put evidence-based therapies into practice. Furthermore, what works in one setting of care may or may not work in another, implying that context variables play a role in implementation. Therefore, there is a need to turn EBP into an active clinical resolution to improve patient care delivery (7).

More focus is needed on techniques that enable educators, education institutions, health services, and clinicians in having the capacity and competence to handle the challenge of providing such EBP education, rather than just focusing on issues like curricula organisation, content, and programme delivery.

Future scope

Incorporating EBP activities into ordinary clinical practice has the potential to increase EBP adoption and involvement. The establishment of computer and internet facilities at the point of care and accompanying content management/decision support systems that offer access to guidelines, protocols, critically evaluated themes, and condensed suggestions were endorsed at the health service level. Nurse scientists have a long history and contribute significantly to EBP and translation science. Nurse scientists are leading the way in translation science, which is still a relatively new field of study.

References

- Salmond, Susan W. “Individual Competence and Evidence-Based Practice (with Inclusion of the International Standards).” Textbook for Transcultural Health Care: A Population Approach. Springer, Cham, 2021. 61-79.

- Speroni, Karen Gabel, Maureen Kirkpatrick McLaughlin, and Mary Ann Friesen. “Use of Evidence‐based Practice Models and Research Findings in Magnet‐Designated Hospitals Across the United States: National Survey Results.” Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing 17.2 (2020): 98-107.

- Lehane E, Leahy-Warren P, O’Riordan C, et al. Evidence-based practice education for healthcare professions: an expert view. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2019;24(3):103-108. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111019

- Schliep, Megan E., et al. “Implementing a standardised language evaluation in the acute phases of aphasia: linking evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence.” Frontiers in neurology 11 (2020): 412.

- Portney, Leslie G. Foundations of clinical research: applications to evidence-based practice. FA Davis, 2020.

- Spanakis, Marios, Athina E. Patelarou, and Evridiki Patelarou. “Nursing Personnel in the Era of Personalized Healthcare in Clinical Practice.” Journal of Personalized Medicine 10.3 (2020): 56.

- Howlett, Bernadette, Teresa Gabiola Shelton, and Ellen Rogo. Evidence based practice for health professionals. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2020.